21 Aug 2003

Census of Marine Life

International Experts Meet to Expand Study of Seamounts and Submarine Canyons As These Nurseries for New Species Become Subject to Commercial Harvest

Amid growing concern over the commercial harvesting of species found in mountainous regions below the ocean surface, more than 30 of the world’s foremost experts are assembling in Oregon August 22-24 to share data and expand global studies of these little-understood ecosystems.

Amid growing concern over the commercial harvesting of species found in mountainous regions below the ocean surface, more than 30 of the world’s foremost experts are assembling in Oregon August 22-24 to share data and expand global studies of these little-understood ecosystems.

Called seamounts, underwater mountains are often isolated and rich in biodiversity, containing large numbers of fish and invertebrates not known to live elsewhere. They typically support long-lived, slow-growing creatures extremely vulnerable to disturbance – among them coral communities and some species of fish, such as the orange roughy.

Their coral communities have evolved over thousands of years and orange roughy can survive 100 years or more.

With sophisticated technology, fishing fleets venturing farther out to the deep sea can locate and fish seamounts and canyons with growing efficiency. There are ready markets for certain fish species that live on seamounts, among them orange roughy, alfonsino and deep water red fish. These new sources of supply, once discovered, are often quickly

decimated.

Bottom-trawl fishing practices are particularly damaging to underwater corals and the thriving bottom-dwelling communities supported by these fragile habitats.

Funded by the Census of Marine Life (CoML) and convened by CoML collaborator Karen Stocks, an oceanographer at the University of California at San Diego, and George Boehlert of Oregon State University, the international meeting in Newport, Oregon is the largest to date of experts in seamounts and undersea canyons. Participants include leading scientists from the USA and Canada, the U.K., Western Europe, Russia, Ukraine, Australia, New Zealand and India.

It is designed as a forum to assess the state of existing scientific knowledge – the “known, unknown, and unknowable.”

It will also work to develop a plan to foster and coordinate future international research, identify priority research questions, determine how to leverage work already underway and organize new initiatives. The results will be important for officials involved in management and policy issues related to these ecosystems.

Says Dr. Stocks: “These are not just threatened habitats; they support new and unique communities that can give us insight into the processes that create and maintain biodiversity in the oceans. In addition to their suspected role as stepping stones for the dispersal of species throughout the world’s oceans, seamounts are also almost certainly centers of speciation – hotspots for the evolution of new species.”

Timing of the CoML meeting in Oregon is driven by new scientific understanding of the seamounts’ importance.

“In the last couple of years major advances have really changed our perspective of how unique these habitats are, and how exciting and informative future research on them will be,” she said. “Recent studies have shown that endemism on seamounts, previously thought to average around 15%, is in fact much higher. They have also turned up discoveries of both very old life forms – hundreds of years old for some corals and crinoids – and living fossils.”

Major issues to be considered include the prediction of species abundance and diversity on unstudied seamounts and canyons.

In the Tasman Sea, studies show unfished seamounts have twice the biomass of fished ones, and only 10% bare rock compared to 95% bare rock on fished sites. Fishing has been most intense for seamounts closest to the sea surface – within 650 to 1,000 meters.

There is growing concern among scientists and conservation groups that these habitats, potentially some of the most prolific and unique on the planet, may be irreparably damaged even before they can be discovered and studied. Most large, shallow seamounts (those over 1000m high and less than 800m below the water’s surface) may have experienced some degree of fishing pressure already.

“What is extraordinary about seamounts is the endemism,” says Frederick Grassle, Chair of the CoML Scientific Steering Committee. “Several major recent studies have found that 30-40% of all species found on Seamounts were new to science, had never been found elsewhere. In some cases, a seamount right next to another may share only 20% or so of the same species.

“At this point, we know that seamounts support large pools of undiscovered species but we can’t yet predict what is on the unstudied ones,” he added. “The tragedy is we might never know how many species go extinct before they are even identified.”

Census of Marine Life: Interim Report to be Launched Oct. 23

Improving understanding of Seamounts is an important component of the Census of Marine Life – an unprecedented collaboration by many of the world’s foremost marine scientists in 45 countries to pool research and create a comprehensive and authoritative portrait of life in the oceans today, yesterday and tomorrow.

The program’s goal is to assess and explain the diversity, distribution and abundance of marine organisms throughout the oceans.

The first CoML interim report will be presented at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, Washington DC, at 10 a.m. Thursday, Oct. 23. The report will review the state of knowledge of ocean biodiversity and how it has been advanced by projects initiated and operated in the first three years of the ambitious 10-year CoML initiative.

Jesse Ausubel, Program Director of the CoML for the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, said seamounts rank high as a research priority.

“As the world marks the golden anniversary of the first successful ascent of Mt. Everest in 1953 by Hillary and Tenzing, we are proud to be part of a similar pioneering effort to explore and understand the planet’s vast underwater mountains” he said.

Background

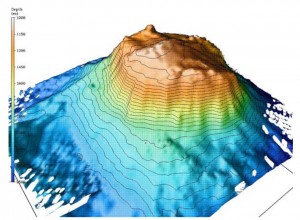

Seamounts, fully submerged mountains or hills rising 1,000 or more meters from the ocean floor, are found throughout the world’s oceans, many in international waters governed by a complex array of multinational treaties. Seamounts often are isolated, which contributes to their uniqueness and diversity of their ecosystems.

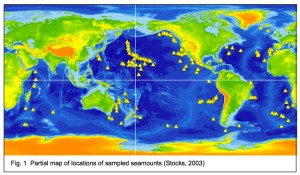

Far more are found in the Pacific than in the Atlantic Ocean, because of increased volcanic activity, and seamounts are particularly abundant in the Gulf of Alaska. The abundance of life on many seamounts compared to the surrounding ocean, providing refuge to rare species, has led to their description as “oases” of life in the deep ocean.

Exploring in the Tasman and Coral Sea area, researchers recently discovered on fewer than 25 seamounts new species in unprecedented numbers, several of them “living fossils,” previously believed to have been extinct since the time of the dinosaurs. In June 2000, Bertrand Richer de Forges and colleagues reported that of 850 species found, 29 to 34 percent were new to science and in highly localized distributions. Earlier exploration of the Nasca/Sala-y-Gomez chain of seamounts off western South America had found levels of endemism as high as 51 percent.

Of the estimated 30,000 seamounts in the Pacific Ocean, only 220 to 250 have been studied, fewer than 150 of them in detail. Only 1,000 seamounts have been named worldwide. Scientists are making progress with acoustics and submersibles, towing deep-sea video cameras from research vessels, and bringing up new findings from their dredges and nets. New analytical techniques are being developed that “mine” existing data to improve understanding of existing deep-sea habitats, and to estimate broader biodiversity patterns.

Fig. 1 Partial map of locations of sampled seamounts (Stocks, 2003)

Fig. 1 Partial map of locations of sampled seamounts (Stocks, 2003)

Seamount species are sustained by food carried by passing currents. Nutrient-rich water is deflected upward by their slopes, picking up speed as it rushes over the summit. Close to the summit, thriving communities of suspension feeders, such as corals, sponges and sea fans, filter organic matter from passing water. Orange roughy, for instance, feed on prawns, squid, and small fish that drift by. Sea spiders and lobsters find refuge in the coral and rock outcroppings. Bottom-dwelling animals benefit from nutrient fallout from above. Whales and tunas visit these undersea mountains on their migratory routes.

Further down the seamount slopes, coral communities become sparser – a phenomenon akin to the treeline in terrestrial mountains, but in reverse.

* * * * *

Additional seamount-related images created by the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) are online at

http://www.oceanexplorer.noaa.gov/explorations/03mountains/background/plan/media/bear.html

http://www.oceanexplorer.noaa.gov/explorations/03mountains/background/illustration/media/alvin.html

For details on or accreditation to the launch of the Census of Marine Life, 1st Interim Report (Oct. 23, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC): Darlene Trew Crist, +1-401-295-1356 or +401-874-6500; dcrist@gso.uri.edu

For additional details of the Oregon meeting: http://seamounts.sdsc.edu/ (under the heading “What’s New”)

CoML sponsors:

Alfred P. Sloan Foundation

National Oceanographic Partnership Program

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

National Marine Fisheries Service

Office of Ocean Exploration

Office of Naval Research

National Science Foundation

Research Council of Denmark

Stavros Niarchos Foundation

Richard Lounsbery Foundation

Japan Society for the Promotion of Science

* * * * *

News release in full, click here

Example coverage: The Telegraph, UK, “Trawlers threaten undersea lost worlds,” click here